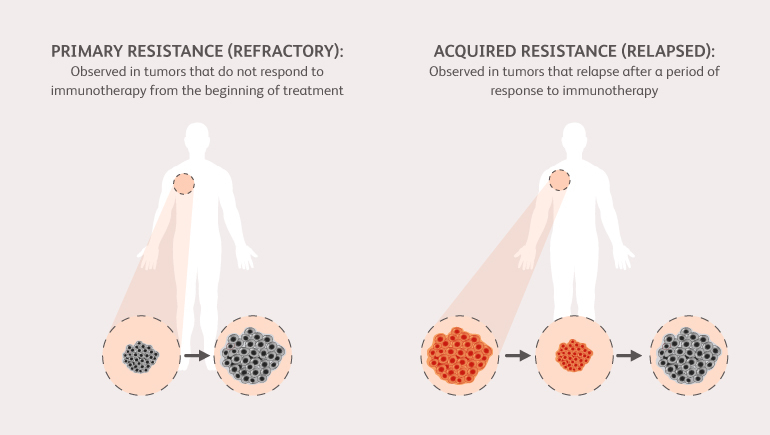

Question: How can biomarkers potentially help match patients to the appropriate treatments for their specific tumor biology?

We hope that by identifying potential factors (called “biomarkers”) associated with either the tumor or the immune response we can identify different mechanisms of resistance. An example of this is the “T cell-inflamed” vs “non-T cell-inflamed” paradigm in which T cell-inflamed tumors have a pre-existent immune response that can be augmented with immunotherapy. As these biomarker efforts become more specific, we hope to identify markers that will help us apply treatments in a personalized approach to avoid treatment resistance.

Question: How close would you say the field is to identifying some of these mechanisms of resistance?

We are all working as fast as possible. While it is hard to gauge when a scientific breakthrough may occur, the field continues to advance with new research each day. As more patients become resistant, it also provides us with an opportunity to build on our understanding for what is happening. For example, at the University of Chicago, we are actively gathering tumor biopsies and blood draws upon resistance to help us study why patients become resistant. Once we have a better understanding of why patients become resistant to treatment and the biomarkers associated, we can hopefully design treatments in such a way that will improve their response.